Eight countries collaborate in the Philippines on the Borges Project

Ich hab' im Traum geweinet

Mir träumte, du lägest im Grab.

I wept in my dream

I dreamed you were lying in the grave.

--Robert Schumann, Dichterliebe

Lying on the floor, sleeping, are the Americans--one in a fitful slumber and the other consumed by a romantic dream. The sound of a wood pipe followed by the call of the kubing, a bamboo mouth harp, represents the music of the

Philippines. We see two men in white body suits, slowly extracting audio tape from each other's mouths. The stage fills with actors…then a song swells from the back of the house, a tenor voice intoning Schumann's Dichterliebe in German. A voice--melodic, poetic--speaks: "He wanted to dream a man. Dream him completely, in painstaking detail, and impose him upon reality." A woman enters, without registering the audience, sets up her laptop and types. Projected words appear: "No one saw him slip from the boat in the unanimous night, no one saw the bamboo canoe as it sank into the sacred mud."

These are the opening words of "Las ruinas circulares" ("The Circular Ruins"), a short story by Jorge Luis Borges, which served as source material for the Borges Project, an eight-country collaboration that culminated in a performance at the 2006 International Theatre Institute World Congress in May, and also opened the Manila International Theaterfest at the Cultural Center of the Philippines. The Borges Project was developed under the jurisdiction of the New Project Group, formed in 1995 with the aim of creating multinational projects. As a U.S. delegate to the Congress and a fundraiser for the Borges Project, I observed this collaboration's development (the third undertaken by NPG) through its final presentation, which opened with the theatrical prologue described above.

Over the past two years, artists in eight countries--Belgium, Cameroon, Croatia, Germany, Japan, Philippines, Switzerland and the United States--created 10- to 15-minute pieces using "The Circular Ruins" as thematic inspiration. The project was originally conceived at the ITI World Congress in Tampico, Mexico, in 2004, then further developed at a meeting in Heidelberg, Germany, in 2005. Line producers based in each country selected a creative team, raised funds and coordinated production details with project managers Emilya Cachapero, from the U.S., and Vitomira Loncar, from Croatia. The pieces were to be woven together during the Manila Congress into a globally resonant production and performed at the closing day's festivities.

The foreigner lay down at the foot of the pedestal. He wanted to dream a man. He wanted to dream him completely, in painstaking detail, and impose him upon reality.

--"The Circular Ruins," translated

~~~~~~~~

by Andrew Hurley

BORGES'S STORY FOLLOWS A MAN, A FOREIGNER, on his quest to "dream a man." This sorcerer, as he is often called, spends 1,001 nights dreaming the man into being. In his first attempt, he dreams an entire classroom of students, but quickly discovers this is not the way to dream a man. He must dream this man organ by organ, hair by hair.

As Arena Stage dramaturg Mark Bly articulated in the program notes for the Borges Project, the story "offers a humbling, cautionary glimpse into the realm of the generative, creative act." The creation theme was the initial attraction for members of the New Project Group. But, in a twist that would surely have pleased Borges, the story served as more than a source for the artists; soon they found themselves, in their creative dreaming, mirroring aspects of the story itself.

In this version of "The Circular Ruins," instead of the sorcerer, there are 22 artists all eager to dream, to create. Like the main character, these artists are foreigners. "I'm sure I would have never come to the Philippines if not for this project," said German team member Alexander von Hugo, echoing the sentiments of most in calling the opportunity a "great gift." Most of the artists had never been to the Philippines before--and even the two Filipino artists were from Mindanao, the southernmost island of the Philippines, far from Manila. Culture shock---and likely jet lag--lulled the artists into a dreamlike situation, in which the only way out was to create--not a man, but a play.

The question was: What would happen when artists from eight countries with eight different translations tried to create connective tissue strong enough to join the disparate parts into a cohesive performance?

He understood that the task of molding the incoherent stuff that dreams are made of is the most difficult work a man can undertake.

--"The Circular Ruins"

Borges Project artists Larisa Lipovac and Bojan Navojec of Croatia.

Philippe Nauer and Dominique Rust of Switzerland.

Chikako Bando of Japan.

UPON ARRIVING IN MANILA, I HAD just enough time to drop my bags in the hotel and wash off the grime from my 23-hour journey before being ushered into a fluorescent jeepney--an elongated, Las Vegasified jeep that transported us to rehearsal (and added a sense of peril to our daily routine). The artists from seven of the countries (the Cameroon team had yet to arrive) had already spent a week rehearsing in Los Baños, southeast of Manila in the province of Laguna. It was there--"in the jungle," as they called it--that the artists presented their work to each other for the first time. U.S. team member Michael John Garcés was impressed by the work and its "diversity of aesthetics and diverse approaches to the material." By the time I arrived, the pieces had been ordered and the artists were delving into transitions--an undertaking that ended up challenging, for some participants, the fundamental aims and structure of the project.

In addition to the 22 artists, the Borges Project had an overseeing director from Germany, Günther Beelitz; a dramaturg and stage manager from the United States, Liz Engelman and J. Paul Preseault; and two Manila-based company managers, Allan and Joyce Manalo. Many countries also brought their own directors. Furthermore, each team came with its own particular aesthetic, making it difficult for Beelitz to come up with a single vision for the piece. He chose to focus on creating bridges between the individual contributions--a decision that received backlash from many of the artists, who were more interested in interacting and experimenting with each other to create new work, than in finessing a compilation of existing pieces.

When I arrived in the rehearsal room, the isolated warm-ups did not reflect the collaborative spirit we had advocated in grant proposals. Some artists exchanged massages, others sat alone reviewing notes while others kicked around a soccer ball and one napped behind the tech table. But despite initial arguments about project goals (product versus process), rehearsals continued and everyone anticipated the imminent arrival of the Cameroonian team. The hope was that their piece, which had singing, drumming and movement, would help offset some of the more somber, stylized pieces. Unfortunately, due to difficulties within the Cameroonian government, the team was unable to attend at the last minute--a heartbreaking loss.

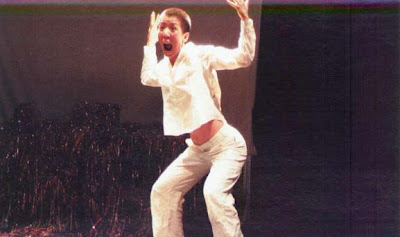

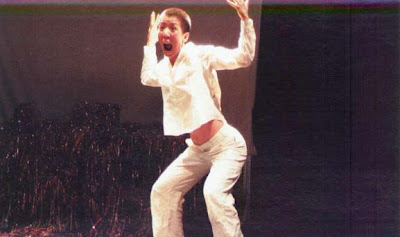

The performance began to take shape: After the prologue, the Swiss team opened with a technologically innovative installation piece in which a video camera moved along a table filled with objects and projected dream-related images onto a screen. With colorful traditional costumes, music and dance, the Philippine piece told of three communities in Mindanao and their struggle to coexist. Focusing on themes of identity and politics, U.S. artists explored the legacy of colonialism and its impact on American identity. Images of destruction and war flashed across the actors' bodies and the upstage screen.

The Croatian piece used an extremely precise movement style, and followed two characters, a man and a woman, struggling to make human contact in an urban environment. Directed in a modernized butoh style, the Japanese piece silently illustrated a being coming to life, learning to stand, discovering her voice, and finally discerning that she could not control her own destiny. The German piece featured an innocent young man undergoing an interrogation by a wily woman; the performers vacillated between German and English. The culminating piece was performed by the single Belgian actress at her laptop, typing to the audience. She used her computer to program a mechanized voice, the Mouth, and explore questions of what it means to "create" using a machine.

Each night he perceived [the heart] with greater clarity, greater certainty. He did not touch it; he only witnessed it, observed it, corrected it, perhaps, with his eyes. -- "The Circular Ruins"

OVER THE TWO WEEKS OF REHEARSAL, the artists developed their own methods of communicating. The artists began to feel creative ownership of the transitions; some took on a directorial role, while others practiced the art of flexibility. The Starbucks across the street from the rehearsal space became an indispensable safe zone at times when tensions mounted. This lingua franca even made its way into one of the transitions: The touching Philippine piece was followed by a condescending applause from U.S. team member Kevin Bitterman, planted in the audience. "The American Dream," he proclaimed, holding his Starbucks cup and introducing the U.S. piece. "You may complain about the American economic domination of your country, but hasn't your life improved since Starbucks arrived?" This was one transition the artists were especially proud of.

The preview performance--arrived at despite the treacherous jeepney's failing transmission and unceremonious backing into a garbage truck--proved the strength in unity. The performance came together as something greater than its parts; the transitions, some stronger than others, did serve as connective tissue. The parts maintained their disparate styles, but an energy passed from piece to piece, even through something as simple as shared breath.

At the end of Borges's story, the sorcerer discovers that although he has accomplished his mission, to dream a man, he is not just a creator but has all along been another man's dream--and he chooses to die. This Borges Project, however, will see more life. New Project Group members--as well as the World Congress's appreciative international audience--were so moved by the artists' dedication and the project's potential that they proposed to expand the Borges Project at the next World Congress in 2008.

By Heather Cohn

Heather Cohn is a New York City-based producer and stage manager and a founding member of Flux Theatre Ensemble. The New Project Group can be found online at http://www.npg.itiworldwide.orq/ More information about the Borqes Project's artistic teams can be found in the international section of TCG's website, http://www.tcq.orq/